article 126: D. Scarlatti, Historian of Spain

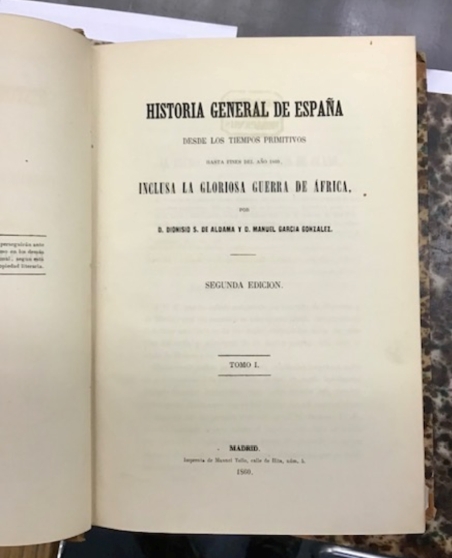

Not Domenico, but his great-grandson Dionisio. As a high government official his father had raised the family’s fortune to its apex; then Dionisio – nomen est omen – wasted it all producing operettas, some of them of his own composition. His lasting monument, which must have also sucked up a mountain of doblones, was a 17-volume Historia general de España (1862).

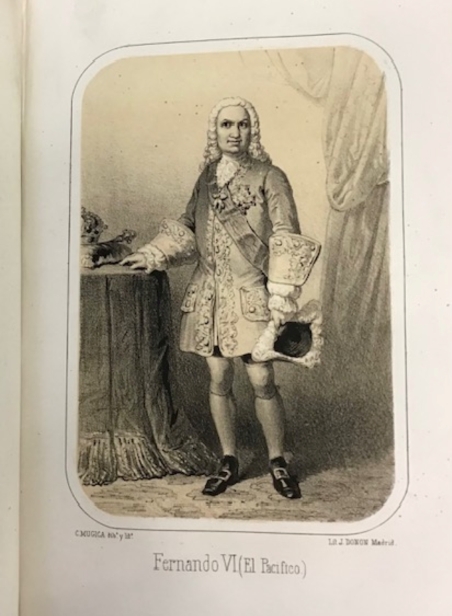

The author signed himself “D. Dionisio S. de Aldama” – his wife’s family name full out, “Scarlatti” as a mere “S.” I had idly hoped to find some new tidbit about his great-grandfather in this magnum opus. But not only does the illustrious ancestor remain absent, the whole history of Spain is presented as an imperialist tract, limited to wars, diplomacy, truces, glorious conquests and an occasional defeat which is always the fault of some perfidious foreigner’s deceit. Music is as good as absent; when mentioned, it is always in connection with royalty. The Historia general puts music in its place: a nearly-invisible entity in relation to the doings of the great and good. In the summings-up of the lives of Philip V and Ferdinand VI, the academies of history and fine arts they founded are mentioned, but there is not a word about music.

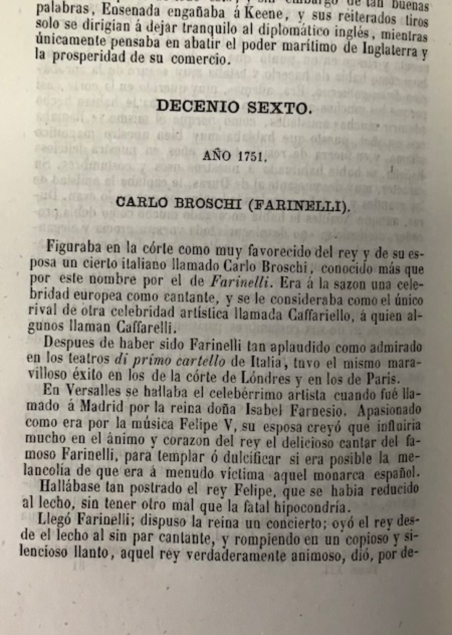

For Domenico’s period, covered in Vol. 12, it appears only twice. There are three pages (242-4) about Farinelli’s good effects on the health of Philip V. Scarlatti de Aldama doesn’t give source references, but these are all tales that were already in wide circulation (especially in Burney and Coxe). And three musicians are named (p. 292) who were active at the dedication of the convent founded by Domenico’s patroness Queen Maria Barbara, the Salesas Reales. The ceremony in the presence of the whole court took place in the fall of 1757, a few months after her music master’s death. The convent, suppressed in the 19th century, still contains the royal couple’s tomb monument.

“[During the dedication ceremony] one heard the imponderable sacred compositions of Nebra, Literes and Corselli, the first and third of these masters, the second, organist of the royal chapel in their time.”

This passage is somewhat confused, and not only in its wording. The organist Literes should have been Antonio Literes Montalvo (died 1768). But his father Antonio Literes Carrión (1673-1747) was the composer of major sacred works. Together with José de Nebra Blasco, he was commissioned by Philip V to write a corpus of liturgical works to replace that lost in the palace fire of 1734 which also destroyed the portrait of Cabezón. Nebra, on the other hand, was not master of the royal chapel, but organist. His harpsichord sonatas are some of the century’s best, and he taught Soler. Nebra also composed the Requiem Mass for Maria Barbara’s funeral (1758). Chapel master from 1738, the composer Francesco Corselli (1705-78) of Piacenza was a holdover from Philip V’s scheming Farnese queen.

It would be interesting to know what acquaintance with “imponderable” sacred works by these three Scarlatti de Aldama might have had. Of course, it would be even more interesting to know what, if anything, he was aware of regarding the only member of his own family to achieve musical immortality. Domenico’s portrait was still hanging in the family residence in Madrid when the Historia was written, but that seems mainly to have been of interest because of his portrayal as a knight of Portugal’s Order of Santiago. De Aldama’s father had gathered information about that for his own application for an honor, but neglected to mention that his grandfather’s keyboard sonatas were in continued demand all over Europe.

If the historian consulted sources like Burney for his pages regarding Farinelli he must have read about Domenico too. Family lore must have held something about the composer. Was it editorial modesty that prevented any mention of him, and even disallowed the writer from naming himself “Scarlatti”? Or was there some lingering scandal connected with Mimmo’s notorious gambling addiction, his repeated indebtedness, and his having been bailed out by the queen and Farinelli? Was he ashamed that his grandfather’s generation, Domenico’s children, were dependent on pensions granted them by Queen Maria Barbara in the short time she was allowed between Domenico’s death and her own?

The musical disaster described in the previous article was more than compensated by a visit next morning to the Bavarian State Library, where, in a rare lapse of German bureaucratic strictness, I was allowed to take the photographs below. And there was more compensation in store, of a more material nature: the last of the season’s white truffles at the Osteria Italiana, which has carried on for over a hundred years as the best Italian restaurant in Munich, in spite of an interval of its being regularly patronized by the worst human being in history. His lap dog Franco sprouted from the attitudes so lamentably dominant in Scarlatti’s Historia general.

December 19, 2023

|

- back -

|